How are foreigners perceived in Uganda?

Muzungus (white people), as we are known, are held in high regard in Uganda. When you explain you’ve come to the country to volunteer, people are truly grateful; it’s quite humbling.

In my first week I attended Luganda language lessons. Just a few words of Luganda here and there have really opened doors for me. Greetings are a crucial start to the day – but be prepared for the roars of laughter when people hear you speak!

Begging is rare in Uganda but you do get regular requests for employment or sponsorship. A gentle ‘no’ doesn’t offend but you’re always perceived as having money, regardless of whether you feel you have it.

In your opinion, what characteristics define a good overseas volunteer?

Volunteers need to be flexible, open minded and resourceful. Working practices in a developing country are very different and even the people you socialise with may be very different to the people you’re used to. I’ve met some amazing people and my friends are of all ages. I hang out with doctors, nurses, speech therapists, teachers, NGO workers, business advisors and safari guides. In the capital of a small developing country you’re very likely to meet the ambassadors, the latest pop stars and visiting celebs. My first ever helicopter ride was over Kampala, after meeting the pilot of the local air ambulance, and last year I even had an Irish MP staying with me for a week!

Volunteers need to be sensitive to the new culture and to spend time listening and watching before you jump in. This helps develop the right local solution to a problem, empowers people and makes the project – whatever it is - more likely to keep going long after you’ve gone. Sustainability of the project and its impacts are key; it’s not just about you having a great experience.

If you’re not sure how to act, watch other people first - although you're still bound to make mistakes, I certainly have! For instance, one time my colleague got very upset when my dog was in the office car; Ugandan dogs never go in the house and the car is seen as an extension of the house. For all my efforts to be culturally sensitive, it just hadn’t occurred to me that there was anything wrong with having the dog in the car.

How can volunteers stay centered with realistic goals?

Don't expect too much from yourself and remember it will take you time to settle in. Over time your understanding of the new situation deepens. It’s always great to keep a diary or a blog to look back on. Having a friend to compare notes with – and to keep you on track – can be a big help too.

If you’re working in a developing country, you probably won’t achieve anything like what you’re used to achieving back home. It is one of many frustrations you have to come to terms with, but it’s normal: you’re coping with a whole new lifestyle and different culture, tiring in themselves, even before you start working. I feel acclimatized now but I do remember that I found the first few months very tiring, just processing all the new things around me, the additional effort it takes to buy food in the market, haggle for purchases etc.

Before you go: Get hold of the job description before you go but don’t treat it as gospel, you may just have to muck in and do whatever task needs doing. Contact volunteers who may have worked for that organisation before; that insight might be invaluable (as well as tips they’ll have on what you can and can’t buy in the local shops!)

When you get there: Don't expect to change the world.

What is the continuing benefit of volunteering abroad after a volunteer returns home?

Volunteering opens all kinds of doors to you – professionally and socially - but it depends on your perspective: some friends back home exclaim “you’ve given up so much,” when I can only see how much I’m gaining. If you're looking at this website the chances are that I'm speaking to the converted!

Volunteering can give you professional and life skills you didn't have before. Many voluntary assignments will actually improve your career prospects. VSO research shows that over ¾ of returning VSOs get better paid jobs on their return. In my case, VSO gave me my first marketing management position.

Working in a new country shows an employer you’re adaptable; you're not afraid of a challenge. Many employers value international experience.

Travel broadens your horizons. You make friends, broaden your network, and you'll want to keep in contact. This can be incredibly rewarding for both you and your local friends. You may want to do some fundraising.

Working abroad gives you a new perspective on life. You will come to appreciate so many things that you currently take granted – and not miss many things you thought you could never live without! Returning home and settling back into your old life isn't always easy though once you have had such a life changing experience.

The new industry ‘it’ word is voluntourism. Do you believe these opportunities are capable of benefiting the communities they aim to serve?

Voluntourism is a great concept. Administered well, these projects have enormous potential in terms of fundraising, networking and connecting real people in the developed and developing worlds.

Unfortunately, like everything in life, there are unscrupulous operators out there.

To make sure your time and money are used in the most effective way, do your research before you sign up and find out how much of your money is going to the project itself. There's always the danger that with our good intentions, we simply reinforce the handout culture, so think how your money and skills will be used.

Tell us a little more about Uganda Conservation Foundation, and what this organization aims to accomplish?

UCF started life in Queen Elizabeth National Park, bordering the Congo (DRC). Activity to date includes: hand excavation of 30km of trench (to stop crop raiding elephants); a network of boat stations and training of 30 marine rangers (arresting poachers and bushmeat smugglers), accommodation for ten rangers in the previously inaccessible northern Lake George (Kibale Corridor) to remove snares, dismantle poacher camps and kickstart recovery of the 400km habitat for wildlife.

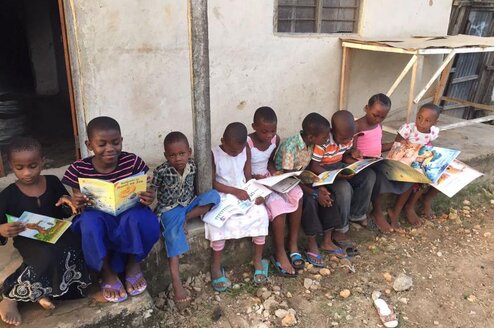

UCF evolved from a research project called Elephants, Crops and People that recorded the worst crop raiding in Africa. Elephants in particular were having a disastrous impact on the community: people were malnourished, and a third of the women were widows, having lost their husbands to Malaria caught while guarding the crops every night. Crop guarding then fell to the children who therefore missed out on schooling. As a result, elephants were being killed in retaliation. UCF employed local people to excavate elephant trenches, since then there have been no reported incidences of elephants being killed, the community is healthier and more children attend school regularly.

Projects in Queen Elizabeth have proved so successful that UCF will soon be starting work on similar practical conservation projects in Murchison Falls National Park, in northern Uganda. It’s exciting to see an organization develop and have an impact.

My role is to raise UCF’s profile, fundraise, communicate with donors, help develop the local team’s skills – and fundraise some more!

A key part of the role is to share skills. Western IT skills, for example, are typically much more advanced than the average Ugandan’s. Many kids don’t touch a keyboard until they go to university (assuming the finish secondary school and many don’t). PC Skills training is rare so people tend to learn from each other. You can really increase a person’s productivity – and appreciate the possibilities of using PCs effectively – through sharing simple PC skills that the average Western office worker takes for granted.

What does the future hold for you and UCF?

This year I will be recruiting and training a Marketing Officer with whom I can share skills.

We are in the process of developing a membership package, too. This is an exciting development as it will help raise the profile of the organization and of conservation generally, raise money and make UCF less dependent on external donors.

I'm not the first VSO who’s wanted to stay in Uganda and have already extended my contract by six months. I'm hoping to develop my travel writing further and I'm even thinking of writing a book now.

Any last words?

Follow your heart, do something you love.